We’re seeing unprecedented volatility in the stock market right now because of President Trump’s trade policies.

The president put record tariffs on the globe, stood firm for a week, and then erased most of them with a social media post, resulting in one of the most volatile stock market environments that anyone has ever seen.

The S&P 500 has been trading like a meme stock, which can be upsetting to some. But it can also be thrilling.

On Wednesday afternoon, the euphoria in the market was amazing. In my personal portfolio, it was the single best day that I’ve ever had, in terms of unrealized gains.

It didn’t last long…

The market reversed on Thursday, giving up much of those gains. As I finish writing this essay Friday morning, I have absolutely no idea where the major indexes will be by the time you read this.

But, for the time being at least, here’s what I do know.

The tariffs aren’t gone. There’s still a 10% baseline policy in place. Chinese tariffs have been increased to 145%. And this is just a 90-day pause, not a cancellation.

From there, the list of things I know gets very short…

Maybe Secretary Bessent can’t make good deals with the 75-plus countries that are allegedly calling the Oval Office. Ninety days is a long time, but who knows what will happen?

Maybe the Musk/Navarro feud will come to a head, and the tariff advocate will tuck his tail between his legs and leave the White House for good. The market would certainly like that.

Maybe Wednesday’s tariff pause is just a ploy by the president to get Republicans in the House to fall in line and approve the pending budget bill.

Maybe the bond market got its way with its tantrum, forcing Trump’s hand. It wouldn’t be the first time. Bill Clinton was famously thwarted from enacting stimulative policies by the “bond vigilantes” during the ’90s.

The now-famous quote from Clinton: “You mean to tell me that the success of the program and my reelection hinges on the Federal Reserve and a bunch of [expletive] bond traders?”

Maybe the tariffs will be back on the table come July.

Maybe they won’t.

There are 75 countries willing to fall in line and one that isn’t…

Maybe it was the “art of the deal.” Trump’s leverage worked on everyone but China and he was happy to take a win.

Maybe he’s listening to former CEO of Goldman Sachs, Llyod Blankfein:

I’m not sure if Trump ever saw this post, but his plan closely resembles the one Blankfein laid out a week ago.

Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

Who knows?

Not me.

Uncertainty Is the Only Certainty

Trump thrives on uncertainty. And as long as he’s in charge, the only thing that I can be certain of is that volatility is here to stay.

The market will always be on edge, ready to crater or rally based upon the whims of Truth Social.

So… what’s an investor to do?

The team has been hard at work providing the best research we can during this time. For instance, Stephen Hester provided several safe-haven sectors in his issue last Friday. Yesterday, Brad wrote about two companies he knows personally that just fell into “fair value” territory. And on Monday, Brad and I shared details on best-in-class utilities provider with two macro tailwinds for our Wide Moat Letter subscribers.

All of these are good options for investors, and we stand by them.

But perhaps the best thing to “do” in times like this is even simpler.

Buy Great Companies… Then Do Nothing

That’s it…

The answer is simple: Buy wonderful companies or even a broad market exchange-traded fund, and then – like a Buddhist monk deep in meditation – do precisely, exactly nothing else.

I mean it.

Don’t try to trade this market. Don’t try to guess the bottom. Heck, don’t even look at your brokerage account if it stresses you out.

You can do these things, but you probably shouldn’t.

Why is that?

Because no one can time the market. It’s a fool’s errand, especially during times like these.

But history shows that the biggest rallies tend to occur during tumultuous times… and investors who miss these days are setting themselves up for failure.

When fear encapsulates the market, it becomes a coiled spring. And without a doubt, fear is ruling the day.

Earlier this week CNN updated its Fear and Greed Index, and it was a 4 out of 100.

For some context, this reading reached a 2 on March 12, 2020. That was, of course, in the midst of the COVID-19 panic. We’re just about there now.

But, of course, we know what markets did after March 2020.

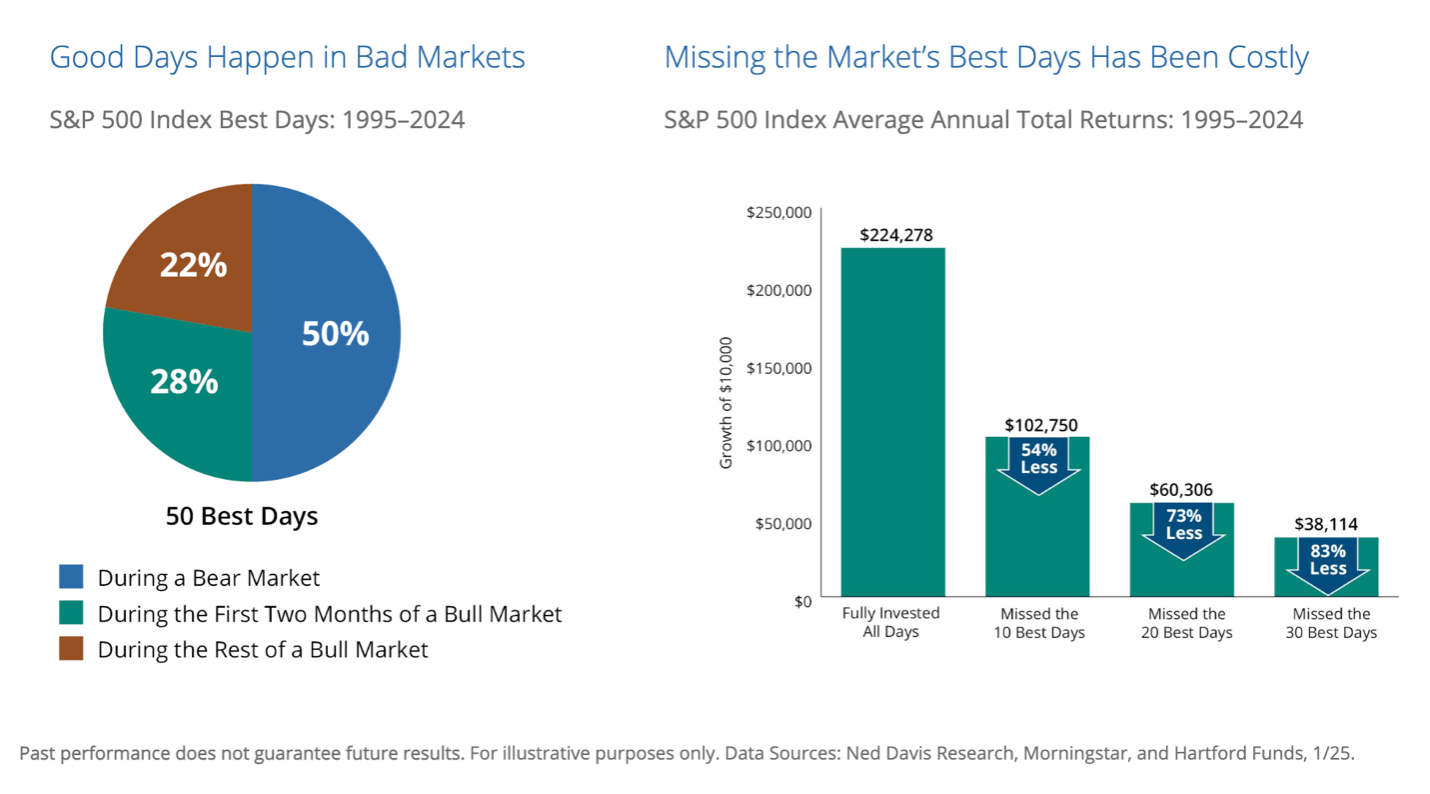

According to a recent study by The Hartford Funds, 50% of the market’s best days occur during a bear market. What’s more, 28% occur during the first two months of a bull market, which, in the moment, is an environment that can still seem like a bear market.

Often, the start of a new bull is only obvious in hindsight. After all, the bull market of 2020/2021 started in the midst of all that fear – March 2020. But absolutely nobody would have believed it at the time.

The penalty for being caught on the sidelines during these best days is steep.

Looking at the chart below, you’ll see that investors who missed the market’s 10 best days during the last 20 years underperformed the investors who stayed fully invested by -54%.

There’s no way to tell when these days occur. But I can guarantee one thing. Disciplined buy-and-hold investors experienced all of them.

Wells Fargo Advisors arrived at similar numbers when analyzing 20-year data.

Looking at annualized total return numbers, the easiest way to underperform the market is to find yourself sitting on the sidelines during the market’s best days.

This isn’t new news.

Here’s some commentary from the CMT Association from May 2008 (at the time, these analysts were trying to keep people calm during the Great Recession).

They said:

The traditional advice of Wall Street has been that “since you can’t time the market” investors should remain invested in stocks at all times to avoid the risk of missing the opportunity for returns. One statistic often cited is that most of the market’s return occurs on a few days and, if an investor is not invested on those days, the investor will underperform the market.

This statistical fallacy relates to the selective use of the extreme numbers in a diverse series. There are approximately 250 trading days each year. In both bull markets and bear markets over the past century, the ‘up’ days represent between 45% and 55% of the days (2002 and 2003 were on each end of the range), nearly half of all trading days. As a result, most of the days offset each other. So regardless of the total return for the year, a small number of the most extreme days will total up to equal the net return for the year–whether positive or negative.

Once again, the only way to know that you’ll experience these few, life-changing days (just like the record-breaking rally that we saw on Wednesday of this week) is to stay invested throughout fearful periods in the market.

I’ll leave you with one final chart today. It’s the best one yet.

It’s from the Hartford Funds report, showing the theoretical value of a $10,000 long-term investment in the S&P 500.

$10,000 invested in 1950 would have turned into nearly $38 million.

That period encompasses a slew of bear markets and a myriad of fearful moments. Yet, by simply staying the course and benefitting from the compounding that occurs when owning blue-chip stocks, a disciplined, patient investor would have become exceedingly rich.

It’s Not Different This Time

Throughout it all… thick and thin… I hope this data compels you to maintain your conviction and to fearlessly own – not trade – the wonderful companies in your portfolio.

No, there are never guarantees of success in the stock market. All equities are risk assets. There’s no way around that.

But, when it comes to fear, I’m a firm believer that, “No, this time isn’t different.”

It never is.

There’s always a reason to be fearful. But American ingenuity has always overcome those hurdles.

I’m still a believer in American Exceptionalism. I still like the long-term prospects of the S&P 500. And therefore, I never want to find myself on the sidelines. The data clearly shows that your best bet for generating wealth over the long term is to stay in the game.

Regards,

Nick Ward

Analyst, Wide Moat Research